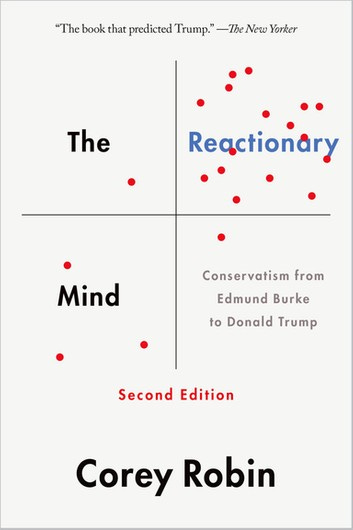

Corey Robin is a political scientist and author of The Reactionary Mind, a book that has shaped my thinking about conservative ideology in ways I’m probably not even aware of. It is now a classic. Professor Robin is also someone I knocked heads with in 2016.

We’re leftists of different stripes (though he might refuse to recognize my leftism). He opposed Hillary Clinton for good lefty reasons. As a pragmatist, I told him, not unrudely, to take his good lefty reasons and jump in a lake. That, however, was then.

Robin’s latest, brilliant and controversial essay in New York touches on something I have touched on here, which is the tendency among some public intellectuals to hype Donald Trump so that he appears on par with Stalin and Hitler. Reams of academic titles routinely situate “Trumpism” in the context of rising global authoritarianism.

Robin notes the overlap and interplay between the interests of the academy, which include public engagement, and the interests of opinion journalism, which include harnessing the authority of the academy for partisan or ideological purposes. He calls this the Historovox: “the complex of scholars and journalists—between the short-termism of the news cycle and the longue durée-ism of the academy.” He goes on:

“When academic knowledge is on tap for the media, the result is not a fusion of the best of academia and the best of journalism but the worst of both worlds.”

This speaks to me as the editor and publisher of a newsletter striving to talk plainly about politics for the benefit of normal people. As you know, I believe the man who campaigned against the weakness of the body politic is the most enfeebled president of our lifetimes. Well, this isn’t just my belief. It is a fact, and should not be surprising.

Trump was unpopular when he took office. He’s unpopular now. He lost the midterms. He lost the fight over the government shut down. He’s going to lose the fight over his emergency declaration. Robin reminds us the president never got an inch of his border wall during the two years his party controlled Washington. I’ve said his only lasting accomplishment was tax cuts, and that’s because the GOP scammed him into believing it wouldn’t hurt the middle class. (It does.) He loses and loses and loses, and yet we keep comparing him to Viktor Orbán and Recep Erdoğan. He’s more like Barney Fife. Only instead of a bullet in the cylinder, Trump’s got a nuclear arsenal.

Robin’s Historovox speaks to me for another reason. We live in a era in which our discourse is polluted by bad actors, corporate interests, and foreign saboteurs. Just understanding what’s true can be an ordeal. While the Historovox aims to address that, it sometimes achieves the reverse. As I argue in “Trump Is Not a Dictator,” it can suggest “someone like Trump isn’t supposed to happen in this country” and imbues him “with a kind of supernatural power. In fact, our system has always been vulnerable to charlatans, demagogues and goons. It’s an imperfect republic, but a republic nonetheless. That is, if citizens do the work to keep it. And we are.”

That’s the brilliant part of Robin’s essay. The controversial part is lumping all scholars, journalists, and public intellectuals together, as if they speak with one voice, as if everyone believed that Trump really was a strongman and were therefore blind to his categorically weakness. Fact is, even as David Frum (author of Trumpocracy), Timothy Snyder (author of On Tyranny), Sarah Kendzior (co-host of Gaslit Nation) and other experts on the history of authoritarianism around the world were sounding the alarm about Donald Trump the Terrible, lots of people were saying, eh, he’s not.

Things could change. But so far, the president has demonstrated he knows little about "the system," has little patience for details and appears genuinely surprised that a president can't always have his way. More importantly, Trump has shown a remarkable tendency for backing off when met by the slightest resistance. Granted, backing off can be prudent. But prudence is not why Republicans and many Democrats voted for this president. They wanted a bull to charge through Washington's China shop. What they are getting is less bull and more delicate porcelain tea cup.

(That’s me on Feb. 13, 2017, less than a month after Trump took office.)

But he is dangerous. That’s the middle ground between these poles.

To be dangerous, a president does not need to be cunning. To be dangerous, a president does not need to be smart. To be dangerous, a president does not need to play three-dimensional chess. With the biggest megaphone in the world, all he needs is the willingness to say anything, no matter how false or offensive or inciting.

With that, Trump can trigger lone wolves around the country, from the Charlottesville killer to Coast Guard Lt. Christopher P. Hasson, who was arrested last week for plotting “terror attacks that he hoped would spark a race war,” drawing up “a target list of prominent cable news journalists and Democratic politicians to be killed” and wanting “to murder innocent civilians on a scale rarely seen in this country.”

We normally equate strength with threats to our lives and liberty. That’s true, but that’s not all. Trump is the weakest president of our lifetimes. He might also be the most lethal in the end. The republic is indeed standing firm, but not without cost.

—John Stoehr

Welcome, new readers!

I wanted to say welcome to our new friends and to encourage them and everyone here to subscribe. By subscribing for as little as $5 a month, you help all of us understand politics a little better. THANK YOU for your support!

John Stoehr

Editor & Publisher

The Editorial Board